The very first week after I moved to Egypt I met a guy named Sherif. I was walking around Tahrir Square in the center of Cairo with some friends, taking in the magical chaos of one of the largest cities in the world and getting accustomed to our new home for the next year. As we strolled along the street in front of the Egyptian Museum, a man approached us. His name was Sherif. He was famous, but we didn’t know it at the time.

The very first week after I moved to Egypt I met a guy named Sherif. I was walking around Tahrir Square in the center of Cairo with some friends, taking in the magical chaos of one of the largest cities in the world and getting accustomed to our new home for the next year. As we strolled along the street in front of the Egyptian Museum, a man approached us. His name was Sherif. He was famous, but we didn’t know it at the time.

Sherif was a true artist, of the con variety, but an artist nonetheless. He was skilled, crafty, and intelligent – a true genius. But he preyed on unsuspecting foreigners wandering around the streets outside of the Egyptian Museum like we were that lovely autumn day.

Sherif introduced himself and was quite a pleasant man. He spoke great English. He was intense but friendly. He seemed genuinely interested in who we were, where we were from, what the thought of Egypt so far, and what all we had seen. He thought we were just coming out of the museum, hence his eagerness to pounce.

Sherif said that he was an Egyptologist. Not just any Egyptologist, but the head of the “Papyrus Institute.” He explained that this research facility was involved in the study and interpretation of ancient Egyptian documents, as well as the restoration of ancient art and artifacts. He said that after 9/11, tourism to Egypt fell off sharply and that scientists like him had taken up tours, sales, and other means of side work to support their families.

Seemed legit. We were, after all, brand spanking new to Egypt and didn’t know any better. He could have said he was the heir to the Pharaonic throne and we’d probably have believed him. Even though we were living there now, we were only a week in, so for all practical purposes we were just tourists in terms of experience and gullibility.

The two friends I was with and moved to Egypt to study Egyptology, so they were eager to pepper Sherif with questions about his profession. Where had he studied? Where had he excavated? What materials did he use for his restoration work? I distinctly remember him uttering a quick reply of “uhh, plaster” to the last question and quickly changing the subject.

Sherif explained that the “Papyrus Institute” he headed was about to relocate to a new facility and that they were eager to downsize their collection, which could not be fully accommodated in the new facility. He offered to take us to see the institute’s storage facility, but first he insisted upon inviting us to tea.

He led us away from the open public areas of Tahrir Squre to the back alleys of a nearby neighborhood. As we meandered through the smaller streets of the hood, we tried to make conversation to mask our nervousness. It wasn’t a scared kind of nervousness, but more of a shy nervousness. After all, we were just out for an exploratory stroll, and now we were suddenly being invited to tea in a local area by an out-of-work Egyptologist. How strange yet cool.

Over tea Sherif got more and more anxious and energetic. He tried to avoid the conversations my friends wanted to have about the specifics of Egyptology and instead peppered us with more questions about where we were from and what we thought of Egypt so far.

Being from the southern United States, I was very unaccustomed to hot tea and opted for a cold soda instead. This seemed to be off-putting for Sherif, who passive-aggressively told my two mates all about how I was making a mistake by not drinking hot tea with them because the weather was so hot and I’d be hotter by drinking a cold beverage. It didn’t make sense then, and it still doesn’t today. But being Southern I was also polite and just smiled while sipping my delicious ice-cold Coca-Cola as we all dripped sweat even in the shade.

During the course of our conversation, Sherif mentioned that one of his sons was getting married the following week, and he insisted we come to the wedding as his guests. When we were done, Sherif also insisted on paying. The tab for three teas and one cola was only about twenty Egyptian pounds, but he wouldn’t let us even attempt to pay.

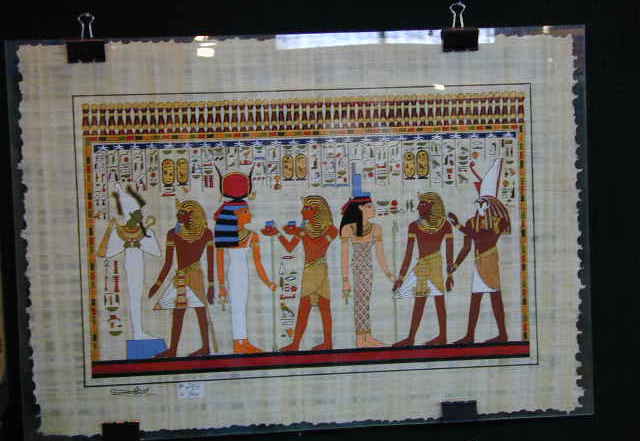

Sherif then walked us further into the hood to a back alley shop that was full of papyrus. There was papyrus on the walls, on tables, stacked on the floor in plastic sheaths, on tables in a second room. It was everywhere. It didn’t seem very institute-y, but it did seem like some sort of storage facility. As we browsed the hundreds of sheets at his insentience, he hovered and commented on each one we pulled out to look at.

After about 10 minutes, he began suggesting ones for us to take home, his voice becoming sterner and more commanding. We were polite for a while, commenting on the beauty of several nice pieces. But ultimately we were uninterested in shopping that afternoon and our disinterest began to show.

At this point, Sherif started becoming more desperate. Perhaps the thought of having spent a half-hour salivating over the potential spend of a fresh group of seemingly fresh tourists was too much for him and he began to crack.

“This piece. This piece is only twenty dollars, my friend. Twenty dollars is nothing to you, my friend. It is nothing.”

The pressure began to mount, both for Sherif and for us. He went around to each of us pressuring us to buy something.

“My friend, you can buy this one. This is one of a kind. Remember we are moving tomorrow. You will never have a chance to buy these pieces again. These prices are so cheap to you. This is nothing to you.”

After several minutes of being in the Egyptian pressure cooker, my friends and I looked at each other and mumbled some jokes under our breath, desperate to find a way to politely get out of this situation.

With Sherif’s continued hovering and whip-cracking, we finally cracked ourselves and agreed to buy one piece each. I can’t remember how much we paid, but it had to be around $15-20 per piece of papyrus.

After we paid, Sherif was as quick to usher us out the door as we were relieved to finally be released. When I asked Sherif how we were supposed to know where to go for his son’s wedding, he hurriedly muttered, “just email me at sherif at yahoo.com.”

I never tried the email to see if it was really him, but I’d bet twenty dollars and a piece of fake papyrus that it wasn’t.

That was my introduction to the highly advanced art of Egyptian tourist scams. Later throughout the year I’d often find myself strolling through Tahrir Square and occasionally I’d see Sherif intensely following a small group of tourists down the street and talking to them.

Sometimes I thought of approaching and warning them about his scam. But it seemed like it would be interfering with the natural process of a kill in the wild. Getting ripped off a little is a part of the experience of visiting Egypt. And Sherif is like a lion prowling the plains of Tahrir Square for unsuspecting American or English or German gazelles.

For the record, that same papyrus souvenir we bought for twenty dollars from “Doctor” Sherif can be acquired for a mere eighty cents from more honest salesmen outside of the museum’s exit gates.

You live and you learn, and the cycle of life – and tourism – continues.