I tend to think of there really being two Old Cairos. The first is, of course, what most people who live in and visit Cairo refer to when they talk about Old Cairo. This would be the area of modern Cairo in which ruins and remnants from many of the city’s magnificent prior eras are situated, including various churches, synagogues, mosques, and the remains of ancient Roman fortifications. But the “other” Old Cairo would be a temporal reference, with “old” here meaning the Cairo of yesteryear. This Old Cairo can only be visited in the black and white photographs that reveal the city’s genteel past – an old and nearly forgotten era when more than just the politics were different in Egypt.

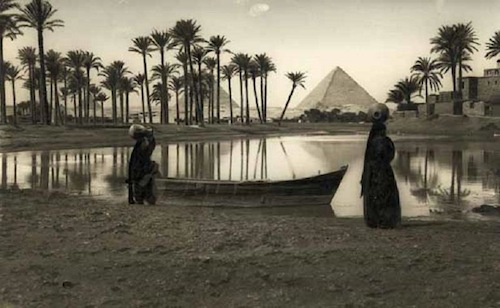

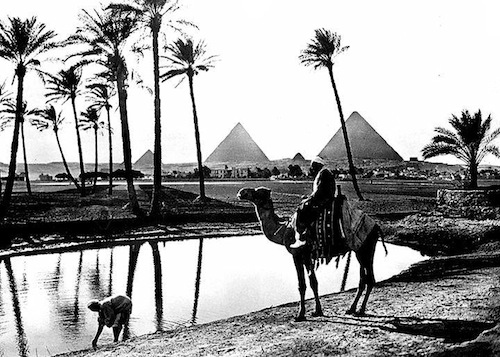

These old photographs of an Egypt long gone provide us with a glimpse of what life used to be like when royalty reigned, when the Nile still flooded annually, and when Tahrir Square was but a charming simple roundabout in the heart of Cairo. More than two revolutions ago (yes, there was another Egyptian Revolution back in 1952 as well that overthrew the monarchy), this was Cairo. And this was Egypt.

In the first photograph below, Egypt’s last monarch, King Farouk, slightly smirks at the camera beside his sisters. In the second and third, we see evidence of the annual flooding of the Nile River, which for thousands of years brought renewed life all along the Nile River Valley and sustained one of the history’s greatest civilizations as it fertilized and re-fertilized a wide strip of land cutting through an otherwise baron desert. What’s especially interesting is that in much of rural Egypt, a snapshot of life looks the same today as it did back then, and the same then as it did hundreds and maybe even thousands of years prior. The rural Egyptian way of life is a simple one, based around faith and family, and it has much more in common with rural and small town life in places like the United States than we typically think

The last photograph below is, of course, of Cairo’s famous Tahrir Square, which one might miss if not for the presence of the distinctly recognizable Egyptian Museum building at center left. Today, Tahrir remains a nerve center for revolutionary, counter-revolutionary, and post-revolutionary activity and political expression in Egypt. Even on normal days it is a bustling, crowded, and unfortunately run-down place, but images such as these remind us that Tahrir – and Cairo – used to be quite different from today.